Sarawak, Spiders and a 160 year old mystery Part 1

By Ray and Angela Hale

Vice Chairman of the British Tarantula Society

THE great naturalist and intrepid traveller Alfred Russel Wallace spent over eight years in South East Asia. During that time he travelled over 14,000 miles and under took over sixty journeys often travelling alone or with one or two native guides.

Being an ardent admirer of Wallace, I have always considered my knowledge of the man and his work to be more than adequate. His place in history although assured has often been overlooked and his work on evolution and particularly his co authorship of the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection with that other great naturalist, Charles Darwin has I am sure slipped willingly from the mind of many an academic. Never the less whilst Alfred Russel Wallace should be remembered for his great work on evolution and his ground breaking Sarawak Law paper of 1855 he is worthy of our respect due to his prolific collecting and his contribution to our knowledge of the flora and fauna of both the Amazon basin and the Indonesian archipelago. However it was the work of a colleague, on that other great naturalist Charles Darwin that made me re-assess my whole perception of not only Wallace but also my own understanding of his work. I realised that all who had gone before me had overlooked a whole area of Wallace’s work. Just has they had with Darwin.

Whilst working on spider specimens at the British Museum of Natural History, a fellow arachnologist, none other than our very own Ray Gabriel, stumbled upon a jar at the back of a cupboard. The jar was simply labeled “Darwin’s Spiders”. It was with great excitement that he opened the jar and peered inside. It is a fact that nowhere in any of the literature about Darwin and his travels does it mention that he collected spiders. There is the scant mention of spiders in passing but in truth Darwin passed them over with haste often referring to them a “brutes” or “denizens of the forest”.

Darwin’s Spiders at the BMNH

At first this might appear puzzling, spiders are plentiful in the tropics and Darwin would have certainly encountered them on his travels, as indeed would Wallace. As to why seemingly neither collected, seemed interested in them or more importantly recorded them one can only speculate. On investigation it soon becomes clear as why this might be. The early entomologists simply lumped arachnids in with insects and it is quite possible that Darwin and Wallace did collect spiders but chose not to separate them. Of course by the 1820’s and certainly by the 1850’s the two groups had been formally separated. A more plausible explanation may be that Victorians where a discerning lot when it came to filling their collecting cabinets. Bugs, butterflies and all things entomological where fine but spiders were viewed with utter disdain. After all these vile creatures killed their prey with venom in the most revolting of manners. No it was simply, as the English would say, “not cricket dear boy”. From Darwin and Wallace’s point of view there was simply no monetary gain to be had on our eight legged friends. The early naturalists need to collect and sell on their charges quickly in order to fund their research. There is another plausible reason as to why spiders were not collected in big numbers. Spiders are in the main nocturnal and the early explorers would have found it difficult to traverse the rainforest in the dark with only oil lamps to show the way. Indeed Wallace himself declared that he had no time to collect at night, as he was busy recording his daylight finds. Beetles and butterflies were active throughout the day and one need only turn over a rotten stump in a forest to reveal a myriad of interesting creatures.

What my colleague had discovered was ground breaking. He lovingly laid out the contents and soon realized that the jar contained not only many specimens of spider but also a pair of fangs that obviously belonged to a tarantula. (Downward striking!). He had, in one afternoon, proved that not only did Darwin collect spiders but also from our point of view, tarantulas. It was a pivotal moment. He published his work in “The Journal Of The British Tarantula Society” (Volume 24 No 3 pp. 90-93) and it was on reading his article that I resolved to prove a similar “modus operandi” for Wallace. In the world of evolutionary science there is much rivalry between the Darwinians and the Wallacites and, albeit it friendly, it nevertheless exists. Many an argument as to whom, when and why as been settled or rather not over a pint. The story of Darwin and Wallace’s “joint” theory of Evolution by Natural selection is well documented and here is not the place to discuss it further.

What is well known and documented is that Wallace was a collector extraordinaire when it came to insects and whilst his numbers of collected mammals was much less it was non-the less equally as impressive.

Over the eight years that he spent exploring the Malay Archipelago he collected over 110,000 specimens of insects, 7,500 shells, 8,050 bird skins, 410 mammal and reptile specimens and numerous specimens of plants and ferns. Of these he kept 3,000 bird-skins plus at least 20,000 beetles and butterflies, as well as some vertebrates and land-shells, for his own private collection.

It is easy in today’s modern politically correct world to view such numbers as excessive and perhaps even unwarranted but we must be careful not to apply our 21st Century morals on a 19th century mind set. Collectors in those early days needed to fund their research and this was a lucrative way of financing one’s work. There were no TV companies with open chequebooks or helicopters waiting to whisk them of to some long forgotten plateau. The working class back in Europe and England were beginning to demand education for themselves and their children and the thirst to see for themselves these weird and wonderful creatures was all consuming.

My mind was made up. I would search the available documentation and literature to see if I could find if Wallace had collected spiders as indeed Darwin had. My first port of call was Wallace’s own masterpiece “The Malay Archipelago”. He makes brief mention of “bird eating spiders” but also makes it clear that he has no time for these “monsters”. Wallace was a meticulous collector and kept detailed notes, many of which survive now in foxing notebooks written in his own, ironically, spider like handwriting.

I began with Wallace’s letters and correspondences all well documented on the excellent Wallace On Line Project (http://wallace-online.org/) and, after some searching I found the following reference in a letter from Octavius Pickard Cambridge addressed to Wallace’s daughter Violet after her fathers death.

In it he states that her father was looking at his collection when he chanced upon a spider and exclaimed, “Why it is my old Sarawak spider” and that he remembered collecting it “as if it were yesterday”.

So it would seem that a spider was collected in Sarawak but when and more importantly from where?

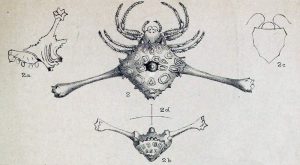

Fig 1: The original drawings of Friula wallacii made by Pickard Cambridge

I scoured the notebooks (on line) that now reside in the Natural History Museum. The records clearly show that Wallace was in Sarawak from November 1854 to January 1856 and during that time he spent his time as a guest of the Rajah James Brooke at his residence at Santabong, collecting at the mines at Simunjan some 50 km outside the city of Kuching and scouring the slopes of Gunung Serambu near the gold mining town of Bau. He recorded each and it seemed every collected specimen on the pages of the now browning books. Yet there was still no record of the spider. One can only assume that Wallace like Darwin did not record the collection of the spider for one or two reasons. Either he felt it unworthy of recoding due to its lack of resale value or he did not know enough about spiders to hazard a guess to its genus and without such information it would be pointless. He would certainly have known it was a spider but the question is would he have had any interest in it? The notebooks whilst of great interest to me were a dead end. After more research I managed to find a copy of the very short paper

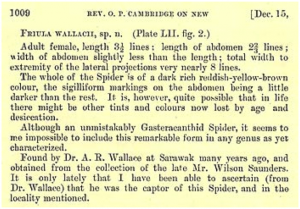

“On some new and little-known spiders (Araneidae) . Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1896, pp. 1006-1012.” by Octavius Pickard Cambridge.

The spider is described as Friula wallacii and is accompanied by a number of excellent line drawings. (Fig 1) I had now found my quarry but where might I find the type specimen today. The plot seemed to thicken but I had the scent and I would not be shaken.

After five years of searching I now knew that he had collected a spider, when it had been collected and where from within a few miles. I needed now to find the type specimen. The drawings were well done but did the spider actually look like this? If it did it was indeed a strange beast. This would be more difficult. Wallace had been in Sarawak for 15 months before moving on to Aru, from here his shipments were all carefully logged and sent to England to Samuel Stevens, Wallace’s agent responsible for the resale of the items. The meticulous logs show that of many shipments sent from Sarawak Stevens had sold one such shipment to one William Wilson Saunders a keen entomologist and president of the Entomological Society. Saunders later fell on hard times and sold his entire collection to Pickard Cambridge. Cambridge was a keen arachnologist and seeing a spider within the collection described it as Friulla wallacii. Ironically he had no idea that the spider was one of Wallace’s when he described it. On Cambridge’s death his entire collection was donated to the Oxford Museum of Natural History. It was here that the type specimen had lay deep within the museum’s vaults for so many years. I contacted my colleague at the museum in Oxford. Again ironically the same person who had discovered Darwin’s spider and after searching the records he supplied me with images of the original type. I had found (with help) the type (Fig 2) and had managed to prove that Wallace did indeed collect spiders. Now all I had to do was find a live specimen in Sarawak………That might prove difficult but the flight was already booked.

Fig 2: The type specimen (courtesy of Oxford Museum Of Natural History)

Sarawak, Spiders and a 160-year-old mystery (Part II)

In my last article I introduced you to the wonderfully exotic world of Alfred Russel Wallace, his travels around Sarawak and our personal quest to follow in his footsteps. Having proved beyond doubt that Wallace had indeed collected spiders on his travels (Part I) my wife, Angela and I needed to travel to the depths of Sarawak, Borneo to the old collecting grounds of this great Victorian naturalist. Our plans was drawn up meticulously and with the help of our good friends on the ground in Sarawak we hoped to retrace Wallace’s steps and with good fortune find the elusive Friulla wallacei spider that only exists as a dead specimen pinned to a board back in the dusty vaults of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in the UK. Wallace had originally collected it somewhere in Sarawak and then sent it back to England where it had eventually found its way into the collection of Octavius Pickard Cambridge, the great 19th Century British arachnologist. Eventually he had bequeathed his entire collection to the museum to await its rediscovery some 150 years later. The decision was made for us and we made ready to travel.

It felt good to be back in Borneo. It has always felt like home to us. My wife, Angela and I have visited it numerous times over the last twenty years and it holds a special place in our hearts. After a brisk passage through customs, where the pretty girl at immigration carried out her official duties and welcomed us back with the Malaysian smile we have grown accustomed to, we were out in to the heat of the midday sun. There to meet us was our old friend, Alex. We had first met him back in 2013 when travelling in Sarawak. He too had a keen interest in spiders and in these days of social media a meeting was inevitable. Now four years later after numerous calls and messages we were finally in Kuching to search for Wallace’s spider.

As we sat in the air-conditioned hotel lobby pawing over maps and photos of the areas, deciding on our plans of when and where we needed to be the atmosphere was electric with excitement. It was decided that the next day we would travel to Simunjan a small town about three hours drive away from the capital. It was here that Wallace had spent nine of his eleven months in Sarawak. In 1856 Simunjan was a rapidly growing mining town and even in these early times a lot of the forest had been removed to allow coal miners access to the hills. It was here that Wallace collected hundreds of beetles, his particular favorites. Due largely in part to the large numbers of felled trees that lay drying in the heat they were indeed numerous. Beetles prefer rotting wood as a habitat. He collected the long horn beetles in great numbers carefully recording each specimen in his notebook. His knowledge of these creatures was immense and he painstakingly identified each and every one to at least genus level before moving on.

Simunjan has much changed now and vast swathes of palm plantation fill the horizon. The exhausted mines have been sealed and only the descendants of the Chinese workers that plied their lucrative trade here so long ago remain, clinging on to solitary existence farms. Nevertheless we carried out an enjoyable but ultimately fruitless search at Wallace’s main collecting site. As the sun began to set we decided to regroup and the following day journey to the second of the sites mentioned in Wallace’s excellent narrative of his time “The Malay Archipelago”. That being Bukit Peninjau.

After spending almost 9 months at Simunjan, Alfred Russel Wallace made a shorter excursion to a small hill 20 km southwest from Kuching town centre. (The area today is known as Gunung Serumbu).

Wallace had met Sir James Brooke, the Rajah of Sarawak in Singapore in 1854 and he was invited to Sarawak to continue his exploration of animal species. Brooke was then 51 and Wallace was almost 20 years his junior but Brooke being a keen natural historian in his own right soon invited Wallace to join him at his summer residence situated on the summit of the hill.

Wallace described the hill in his book The Malay Archipelago.

“On reaching Sarawak early in December, I found there would not be an opportunity of returning to Singapore until the latter end of January. I therefore accepted Sir James Brooke’s invitation to spend a week with him and Mr St. John at his cottage on Peninjauh. This is a very steep pyramidal mountain of crystalline basaltic rock, about a thousand feet high, and covered with luxuriant forest. There are three Dyak villages upon it, and on a little platform near the summit is the rude wooden lodge where the English Rajah was accustomed to go for relaxation and cool fresh air.”

Today the entrance to the site is reached by road and easily missed but Wallace would have arrived by river and disembarked at the village of Siniawan. From here the Rajah’s loyal Dyaks would have led him to the cottage. On our visit we too had the advantages of guides although I suspect it was their youthfulness and all the technology that they bring with them today that facilitated our journey rather than their ability to “read the land”. Our very young guide stared at his phone as we drove along the main road and he shouted directions as his GPS signal beeped at him. Missing the turning would prove a lengthy exercise, as the roads are interminably long. However turn we did and began to climb up a very steep and narrow road. It looked to all intent and purpose that we were driving through someone’s property and one or two puzzled homeowners stared at us nonchalantly as we crept past. Soon the road opened out and we found ourselves before a large wooden building with a huge sign that proudly proclaimed “Rajah Brook Restoration Project”. This is the site of the original Brooke Cottage and although now the original structure as long gone the area is undergoing a complete revamp. The first phase of Sir James Brooke Cottage and Wallace Trail restoration project at Bung Muan, Bukit Peninjau in Bau started a few months before our arrival and is due for completion by 2019.

We abandoned the car in the empty car park and entered the ramshackle wooden building through the open door and looked at the walls covered with architectural drawings and photographs. There were posters highlighting some of the insects that could be found in the area. A toothless old man appeared at the door, smiled and conversed with our guides in Malay. He explained that there was much work going on and that the trail was wet and difficult at this time but we were welcome to explore but we must be careful. We showed him the photo of the original Friulla wallacei and asked if he had seen anything similar. The truth is that to most people a spider is a spider and although he said he had I had my reservations. A group of workmen digging what seemed to be a pool waved at us and smiled as we stood chatting. The old man gave us bottles of water and we signed the visitor book and prepared for our assault on Gunung Serambu. We waived back at the workmen and began our ascent. The terrain was difficult and as the old man had rightly predicted very wet. The incline was exceptionally steep and walking sedately would not be an option. This was going to be tough. The path was overgrown as the forest attempted to reclaim its domain but nevertheless we soldiered on. Being an entomologist has its advantages in situations like this. The main one is that you are at least staring at the floor as you walk so tend to see the pitfalls more than an ornithologist might as they look to the heavens. You also see more things that others might. A tractor millipede (Polydesmida sp.). One of hundreds that we were to see marched nonchalantly across the path. Giant orb weaving spiders of the Nephila genus hung motionless in large messy webs waiting for their breakfast to arrive whilst colourful tiny jumping spiders eyed us curiously as we encroached on their micro world. We were of course still looking for our spider but we were content to settle for any arachnid that might appear. Friulla wallecei is a Gasteracanthid type spider. They are also commonly called spiny-backed orb-weavers, due to the prominent spines on their abdomen. These spiders can reach sizes of up to 3 cm (1.2 in) in diameter (measured from spike to spike). Although easily spotted it is however prudent to be aware of the preferred habitat of such spiders before you begin your quest. Masteracantha acuata for instance is known to set its web either near to or above rivers. It will sit in the centre in clear view and wait for any flying insects to rise form the river edge. They are certainly water lovers and all examples that we have found over the years tend to follow the same modus operandi. To this end the trail up the mountain followed the course of a slow flowing spring as it cascaded down the slope. We were hopeful that if our spider were here then it would be close to this course. We soon came across Gasteracantha hasselti and two other thorn spiders but no wallacei. The path became even steeper and the dense flora that had covered the lower path soon thinned and became sparse clinging to huge granite boulders petruding from the ground at obtuse angles. These rocks glistened with water as it flowed ever down. The path led us between two huge outcrops and then climbed ever higher. At a convienet point we stopped to refresh ourselves with the water and to take a moment. It was then we heard voices and to our surprise three Dyak tribesmen appeared from the twisting path above us. Two of them clothed in loincloths the third with a pair of shorts they explained that they were working on the restoration of the cottage and were on their way down for more wood. We asked how long to the top and with a smile one announced “ for us? Twenty minutes…the speed that you walk about two hours” It was a great source of amusement for them. I did however noticed that none of them wore shoes of any kind and they walked over the wet rock with ease their feet appearing to mould to the surface. Despite our “superior” walking boots we could only tread carefully as we slipped and slid in every direction. Wishing us well the three men continued on their downward journey and we continued on our ascent even more determined than before. We found a scorpion (Heterometrus sp entangled in a spider’s web but still alive. Even bigger Nephila species surrounded the path; giant hammerhead worms (Bipalium genus) squelched their way over the soaking trees. Beetles of all shapes and sizes scurried to and fro (Wallace must have been in his element here). Grasshoppers and crickets chirped loudly and there were ants a plenty but no Friulla wallacei. After another thirty minutes we made the painful decision to begin to descend. The weather was turning; rain had started to fall albeit lightly however we all knew that in this region torrential rain is never far away. We were not downhearted and turned back down the path. Imagine our surprise when after ten minutes we were met by the same three Dyaks on their way up. This time however they each carried half a dozen very long planks perched on their shoulders bound for the cottage site. Arriving back at base camp we decided to take a good look around the area. It is often the case that insects and spiders prefer the company of mankind. Humans are dirty creatures. We throw our food and waste away anywhere and this attracts insects. This in turn attracts spiders and the spiders bring birds. It’s all part of the food chain. We were not disappointed. Very soon we found many species to amuse us. A fine St Andrews cross spider (Argiope sp.) sat perched in her web and a number of beautiful butterflies floated by on wings of gossamer. All in all the day was success but still no spider. Bidding the old man farewell with a promise to return one day we set off down the hill to begin the drive back to Kuching.

On the way back to Kuchng from Gunung Serambu you can visit the amazing fairy caves and we did indeed spend time there but as a spider hunter it proved disappointing. The caves are obviously well trodden and the insect and arachnid life tends to be limited to cave crickets and the occasional Meta. sp. Never the less it is worth a visit and I would recommend that if you are Kuching you make the trip. Situated 5km for The Fairy Caves are the infinitely more interesting (to an arachnid lover that is) Wind Caves Nature Reserve (also known as Lubang Angin). This small but ancient site provides visitors with an authentic, but relatively safe, caving experience in pitch black, bat-infested tunnels. You can of course just explore some of the 6.16 hectares of forest and rivers in the protected reserve surrounding the caves. We arrived late in the day and made our way around the boardwalk that leads to the caves. The forest is awash with insect life and in the bushes that are neatly planted around the entrance we found at least twenty Macrocantha.arcuata . As I climbed over the low fence to get a closer look a young Malay family entering the park gave me a strange look but I was by that time on a mission and nothing could stop me. In one of the webs a beautiful blue butterfly struggled to free itself as its nemesis approached from its lair. I admit to being quite pleased when just as the jaws of death were about to close on its prey the beautiful creature escaped and flew away. We had been told that there were tarantulas in the cave and we set about finding them. The path through the caves are made of sturdy wood with good hand holds but a quick search with the torches revealed that the floor of the cave was made of a soft sandy substrate. Sure enough there in plain site were burrows. They were all about 1 inch in diameter and most of them had a small tarantula sitting at the entrance. They looked like Phlogellius species but any chance of getting closer was out of the question. To be honest I didn’t want to. I am content to record and photograph. One should also bear in mind that this is a protected Nature Reserve and the stringent laws that protect it.

As the darkness began to fall we headed back to the relative comfort of our hotel and after a quick, much needed, shower we reconvened in the bar to compare photographs and discuss the next days adventures. The next morning I had an appointment with Dr. Charles form the Sarawak Museum of Natural History. We had met Dr.Charles on a previous trip and were keen to rekindle our friendship. We made our way across the busy road and entered the air-conditioned offices. We were ushered to the office being followed by an entourage of young Malays all busily taking photos of us. We wanted to reaffirm our contact with the Museum and in particular Dr.Charles as having a relationship with the local experts shows both respect and helps to open doors. The second reason of my visit to meet Charles was that some months before whilst giving a lecture in the UK on Borneo a charming lady called Doreen had explained that she spent much of the 70’s in Kuching where her husband was an engineer. Her husband had sadly passed and she was moving house. She told me that she had over 2000 slides from the period and asked if I would be interested in them. I contacted the Sarawak Museum and they accepted my offer to donate them with great joy. Although Dr Charles is and entomologist specialising in sea invertebrates I believe he was ecstatic with the slides and as we chatted he eagerly held one after another to the light and cooed with delight. We said our farewells and made plans for our next adventure. Nothing could prepare us for the events of the next day and although we were still searching for our quarry it is safe to say that we had an experience that we will never forget………coming soon Part III.

Sarawak, Spiders and a 160 Year Old Mystery (Part III)

In my previous articles I told the reader of our attempt to demonstrate that whilst it had been proven that the great naturalist Charles Darwin had collected spiders on his travels it was also true that his co-author and contemporary, Alfred Russel Wallace, had also collected arachnids throughout his travels in Indonesia. We had shown that Wallace had indeed collected a spider and that later Octavius Pickard Cambridge had described it has Friula wallacii and that Wallace himself had identified it as his. My wife, Angela and I had then travelled to Sarawak to attempt to follow in Wallace’s footsteps where we hoped to find evidence that Friula wallacii still existed today. After a fruitless visit to Simunjan, an area where we knew Wallace had spent nine months; we regrouped and planned our trip to Bukit Peninjau. This was an area West of Kuching; we knew Wallace had spent time there with Rajah Brooke at his summer retreat. Whilst this had proven to be a successful trip with regards to finding spiders and wildlife in general, our quarry still eluded us. We were disappointed, but not disheartened, with the trip and despite our plan to climb to the summit of Bukit Peninjau being curtailed by torrential rain we once again returned to Kuching to plan our next adventure into the interior. In this the final part of our article I will tell the reader of an amazing discovery made after a chance meeting.

There was a definite air of gloom in the vehicle as we made our way from Bukit Peninjau along the main road back to Kuching. Our original intention to climb to the summit to visit the site of Rajah Brooke’s Cottage had been postponed as heavy rain began to pour. The path soon became a torrent of raging water and the already slippery boulders became decidedly lethal. We made the decision to retreat for safety reasons and as we carefully picked our way back down the hill the mood was to say the least somber. We were exhausted, dejected and wet as we returned to the vehicle. As we washed off our mud-covered boots we chatted about the day and the more positive things we had discovered. Scorpions, thorn spiders, tractor millipedes. They were all of interest to us. We had found some interesting creatures of this there was no doubt but we were still missing the final piece of our puzzle. In a brave attempt to lift our spirits one of our colleagues asked if we were interested in flowers. A strange question I thought but nevertheless both Angela and I answered in unison that we did. He explained that he had a friend who ran an export business and that he grew many types of exotic flowers and would we like to see them. We could freshen up at his property and relax for a couple of hours before returning to Kuching. The day had been enjoyable, although unsuccessful so far, so we readily agreed to go along. We soon found ourselves pulling off the main road and through two huge iron gates. A man with a beaming smile and baseball cap greeted us with an equally enthusiastic handshake. He introduced himself as the owner and beckoned us to join him. He bade us sit on his wooden porch whilst his wife appeared and offered us all refreshment of green tea. Throughout all of my travels through South East Asia, the one thing that has never ceased to amaze me are the people. Their unending hospitality and overwhelming friendship fills ones very soul with joy. After enjoying the delightful repast our host excitedly showed around his site. We were greeted with row after row of covered exotic plants of every colour, green and red bromeliads, ferns of every size and strange succulents and pitcher plants all covered with flimsy green mesh to protect their delicate leaves from the mid-afternoon sun. His enthusiasm in showing us his collection of orchids was infectious. We chatted for a while enjoying his hospitality and then he said it.

“So, I hear that you guys like spiders?”

We nodded in the affirmative whilst sipping the fragrant green tea.

“I know where there are some as big as your hand…care to see them?”

My initial thought was that as spider hunters we had heard this type of thing before and they normally turn out to be nothing more than giant Nephila sitting in their huge webs. Impressive they may well be but they were not what we had come to look for and we had seen our fair share of this spider already this day. He smiled and assured me that he knew the difference between orb weavers and tarantulas and that the ones he had found were most definitely tarantulas. Our hearts lifted as he went on to say that they could be found inside a cave about a kilometer away. We prepared our kit, checking our torches and pulling on our soggy boots. He picked up a machete and we set off on foot. I remember thinking to myself; “I am about to enter a cave with a man I have only just met who is carrying a big machete. Oh well!”

He told us that the walk was easy but that we would have to cross a river and depending on the depth due to the rain it may not be accessible. After about twenty minutes of following a trail through dense undergrowth we arrived at the river’s edge. The river was indeed very high and to attempt a crossing would be madness. It was agreed we would return next day. The light was fading and we felt we should be better prepared for any exploration of this nature.

After a sleepless night we once again arrived at the edge of the river and, as our guide had predicted, the river had dropped enough to allow us to wade across. It was now about 3ft deep but the sides were soft mud so we knew we had to take care. Our new friend went first followed by our young guides, Angela and then myself. The water was warm and our feet sank deep into the silt as we pushed our way against the strong current. As we waded across, a water snake floated nonchalantly past and one of our team hurried off in earnest pursuit. Arriving on the other side we found ourselves standing before a huge cavern entrance. Amazingly from the other side it was barely visible being covered by tall trees and foliage but now it loomed above us like a huge open mouth gaping at the sky.

We entered the chasm and looked around in the gloom, allowing our eyes to become accustomed to the darkness. It was obvious that the cave was well visited by local youths. Dead campfires were dotted around the entrance and discarded plastic bottles and cans littered the floor. Graffiti covered the walls although it did amuse me that some of it was dated as being from 1958. Tomorrows cave art antiquity perhaps? I confess I did not hold out much hope. Undaunted, he signaled for us to follow him as he walked to the rear of the cave. He stooped down and disappeared into the darkness. Hesitantly we followed and soon the tunnel began to narrow and the dim light from the entrance faded until disappearing altogether. The roof lowered and we found ourselves on our hands and knees crawling along the narrow passage in total darkness, lit only by the dim beams from our head torches. I voiced the question as to how far we had to go as I admit that I am not keen on enclosed spaces. A cave cockroach ran over my hand and a Scutigera centipede sat above my head. My question fell upon deaf ears and we pushed on.

After what felt like an eternity we emerged into a large, dark cavern. Our voices resonated in this huge cave. Our head torches illuminated the walls but did not reach the ceiling of this cathedral of stone. The air was hot, humid and the gloom all-consuming. I reached for my powerful torch at my side and as we all switched them on the chasm was flooded with light. It was indeed a magnificent site to behold. I stared at the floor as my jaw almost hit it. Surrounding me were hundreds (and I mean hundreds if not thousands) of burrows all lined with pure white silk that radiated over the edges. They ranged from the width of a pencil to ones a man could easily put his arm down (should he off course wish to do so). The burrows were in close proximity to each other. Along the walls at ground level where the substrate met the vertical wall one could see long silk sock burrows covered with detritus whilst sitting on the walls were a number of large tarantulas. This should be the stuff of nightmares for some but to the seasoned archnohunter it was heaven. The habitat of the spider is a very deep cave well below ground level situated in a small de-forested area now covered with secondary forest. The cave sits in a limestone outcrop that has now been isolated as it became surrounded by civilization. It is in close proximity to human habitation but far enough away and inaccessible enough to avoid interference from anyone other than the most determined visitor.

A small gecko sat eying us carefully, motionless whilst a vinegaroon made a dash across the floor after we had evicted him from his overturned home. Cave crickets seemed to abound and it was obvious that this was the main food source for the spiders within the cave. We agreed that we needed to see one of these larger tarantulas in the light to be able to photograph it adequately and to ascertain its genus and species. I would point out that we are not collectors. We have no interest in capturing these spiders for export. Our passion is finding new species and furthering our knowledge of these much-maligned arachnids. Should we find one then we all had the understanding that we would return it unharmed. We did however need to photograph it in order to assign it to a family. By doing so we hoped we could allow the community within to remain untouched forever.

After two hours the air in the cave became oppressive, with no visible source of external light the torches were in danger of failing. There seemed to be no obvious influx of fresh air apart from the narrow passage through which we had entered. The water that hung in the air was clearly visible in the beams and we had begun to start feeling nauseous. It was time to leave. We collected our kit, replaced the rocks we had moved, said a few words at the makeshift shrine and we made our way out back along the narrow passage. As we crawled further we felt the strong current of air blow over us from the entrance. It felt good as we emerged from our makeshift tomb into the light again. We sat and pondered on our find. We held the plastic container in our hand and all marveled at this tarantula. They say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder and to many I suppose this would be just another dull brown spider. It is not colourful, nor is it I suspect collectable. Something in its favour.

I immediately noticed that the eyes were white and milky. It had made no response as we shone our torches over it in the darkness and I wondered if this animal was on the way to losing its eyes or indeed it had already lost its sight. After all it lived in total darkness and would have no need for vision. It would detect its prey by the setae on its legs as the current moved gently across them. To an arachnologist finding any spider in the wild gives a monumental feeling of pride but to find what is quite possibly a new species or maybe even a new genus is the eureka moment we all seek on our travels.

We carefully photographed the spider in daylight. It made no attempt of aggression towards in fact it was remarkably placid. I would have liked to spend longer examining the spider but time was not upon our side. Having satisfied ourselves with our photographs our host returned to the cave and returned the spider to its original home. It was agreed that we would return the following year and revisit the caves to make further more in depth observations. This visit had been fleeting, it was unexpected and we were ill equipped for the expedition. We had simply run out of time and we were due to return to the UK the next day. The indigenous researchers will work upon the spider soon and hopefully we will be able to ascertain if it is a new species and if so to what genus it belongs. The smaller species within the cave looked at first sight like a Phlogiellius sp. but it would be impossible to say with certainty unless collected and taxonomically inspected. It is my hope that this cave system stays undisturbed for the foreseeable future and that any visitor affords the cave and its occupants the respect they deserve.The next day we said our farewells to our young team of budding arachnologists and we agreed that they would continue their work both in the cave and in other areas. As we climbed into the taxi our Malaysian friends leaned forward and said:

“Next time we will show you another cave…. the spiders are even bigger”

They roared with laughter as we drove off to catch our flight. I would hold them to that and as we entered the airport lounge I had already checked the flights for the next year and started to make plans……….Kuching here we come (again)!

Addendum

In 2018 we returned to Sarawak and captured more photos of this amazing creature. The cave had remained undisturbed and the population seemed to be static. It is our hope that it stays this way for many years.